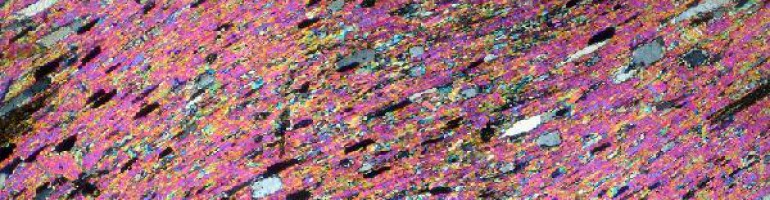

Protesters Standing Before the Brussels ‘Bourse’ or Stock Exchange in their Syndicate Colours

Of course I did not get to Zilverhof by 8.30 in the morning. In fact it was after ten o’clock when I eventually rolled out of bed, and near eleven by the time I had finished breakfast and got onto my bike. You can’t riot on an empty stomach – but actually, now that I come to think of it, that’s exactly how most riots start.

When I cycled passed the window of Zilverhof, I saw Jo through the kitchen window, standing still, a little bow-backed, with a cup of coffee in hand. His stooped form was magnified by the window like a fish-lens. I knocked on the door.

“Ah, you made it!” he said excitedly. “Do you think we can still make it?”

“Yes!” I replied. “I have read that the march really starts from 2 in the afternoon. We have plenty of time.”

Without further ado we jumped on our bikes, our metallic horses – Jo’s held together by bits of gaffer tape – and galloped towards St Pieters Station.

On y va! Or as they say in Flanders, the roll-call of the socialist party: Vooruit!

As we accidentally took the long train to Brussels Centrale, the Mondial Clock on the station wall announced that it was 2.30 by the time that we arrived in the country capital. But in a way it didn’t matter anymore, manifesting against the powers that be suddenly and draconian austerity measures, seemed of secondary importance to the game of getting to know each other. I brought out a block of cheese and some tomatoes that I had brought with us to picnic on. I had forgotten my pocket knife, so we simply tore off hunks of cheese and handfulls of bread. I was enjoying this game of down-and-out – a game I could play only half seriously. After all, in Belgium I am not rich – I live on a waitress’s salary – but I am also not as poor as Jo. It reminded me of travelling in South America – the go-to cheap vegetarian sandwich. It’s amazing that almost wherever you go in the world (except for Asia) you can knock yourself up a cheese and tomato sandwich with almost no difficulty.

What did Jo speak about? His life before Ghent in his native city of Brussels. The bad friends he had had there. The life he left behind.

I burnt all the bridges I had, he said, I even sold my library.

I came to Ghent with nothing. I burnt all my bridges too, I replied in turn.

From that moment onward, I knew there was no going back. What happens when fate places two lost souls on the same train to Brussels? Magic – but also, of course, trouble.

But I was not to know that then, although in a way, somewhere in my heart I also believed I did. Suffice to say, from that day on, a seed was planted that invisibly, embedded its secret life within me.

When we eventually got to Brussels, well-lunched and full of excitement about each other; I had almost forgot that our nominal goal of the day was to be political: to fight, to resist, to stand up to tyrants and bullies. So in a way, my inadvertent lack of mental preparation, the secret, hermetic place that I had disappeared off to with Jo beside the shifting panels of a train window, meant that the scene of epic national turmoil and resistance outside hit me with greater force than it otherwise might have done.

As we snaked along the rich, imperial streets surrounding Brussels Centrale, dipping ever so gently towards Brussels’ first boulevard, the Beursplein, the various streams of human bodies into which we ran, like estuaries of a great river, gradually increased in velocity and number. By the time that we at the Beursplein, the central conduit for the demonstration, the bustle and business in the streets was impossible to ignore. Human bodies stood everywhere: dockworkers, teachers, artists and steelworkers, all arrayed conscientiously uniformed in green, blue and red plastic tunics.

The vests show what syndicates the workers belong to, Jo explained to me. It was, after all, a worker’s strike, a labour strike.

As Jo continued to offer an explanation of Belgian’s complicated political system led by central-rightist Prime Minister Charles Michel– its various strands, member and constituent parties with their attending colours and mandates – so as to help me decipher the colour-coded crowd – my senses where somewhere else or perhaps, more accurately, everywhere. My ears were trained like a marksman’s on the frequent hissing of firecrackers and flares that were let off by invisible members of the churning crowd. The crackers added palpable tension to the march, seeming to shore up the dormant, but existent violence, underlining everything. These little white, skittering bolts were going off in all directions. Who knew if one would catch you, or zig-zag between your feet? Or sting your toes or singe your hair? It also endowed the march, for me, with a distinctly continental feeling. I wasn’t use to these tricks from the UK protest scene.

Let’s try and get to the back, shouted Jo, so that we can see it all!

I liked this idea – the desire to have a kind of totalizing, complete view of the march. As we dashed about, weaving between the tide of protesters, taking side roads as short-cuts, occasionally sitting on a pedestal on the road and sharing a roll-up, Jo became madly obsessed with statistics.

They say in the tabloid press that only 20,000 are going to come out on the streets today. But they’re lying, they are saying that to put others off and convince them that it’s not really a true protest. But they’re wrong. What the government are planning to do is really awful – it would change Belgium forever. Everyone needs to be on the streets today.

Jo was right, the further we went, counterflow against the march, swimming against the current of human bodies, the more I realised the enormity of the demonstration. It was certainly on a national scale. The level of organisation was also very impressive.

I think it’s at least 80,000! Cried Jo excitedly, like a child.

Yes, on and on the river ran. Hanging strangely above this banded mass of humanity, loomed the huge insignia of Macdonalds, and the logos of Belgium’s largest shopping meccas, clothes stores and supermarkets.

This protest is a demonstration against these things as well, I thought, it’s all connected. It’s not just a political game. We are fighting for a much more fundamental principal, one of humanitarianism against capitalism and profit; representing the belief that a country should do what is in the interests of the people who live in it, and not what is in the interests of the rich or of multinationals and franchises. Hence the Belgian slogan designed by the artist syndicate: Hart voor hard it read. Pithy. Nice. “Heart over austerity.”

In the end it must have been at least an hour before we managed to circumvent the entire march, and snake back to its tail, or rather, find the end of the snake’s tail. Oomboros. As we walked we experienced many different ‘waves’ of the crowd, densely packed areas full of stout-bellied factory workers and middle-aged women with iron-grey hair, areas were the dread-locked young marched and banged drums. In other areas, the lawn of people and revolutionary spirit were more sparse and spread thinly – so that at points the crowd appeared to be more like apathetic pedestrians than a protesting band enlivened by common purpose and determination to succeed.

On the whole I believe that the march was slightly less ‘alternative’ than I expected. I imagined, that as with pro-Palestinian demonstrations or pacifist demonstrations, that there would be more tye-dye, more “sit-downs” or creative forms of demonstrative activism. I didn’t see this margin there – what I saw that day, was, perhaps more meaningfully, the average ebb of the population. It was a crowd amassed from ordinary people, not just the young or radicalised. This is what made it a powerful symbol of frustration with the new government – because everyone was there; even, as Jo, pointed out to me, as he gestured to a small group of people brandishing red tunics – members of their own party. This demonstration was a powerful symbol of rejection and anger. But also, for me as someone from the UK, a great example of how an industrial strike can occur that expresses visible, well organised discontent, aligning professional and labouring under a coherent political slogan. In Belgium the industrial working class still wield real political clout.

As soon as we had reached the end of the march we became bored of it.

Let’s return to the middle of the crowd, cried Jo impetuously.

Of course I agreed. And so our singular trajectory continued – not counteracting the crowd this time, and not running in tandem with it – but rather, scurrying between landmarks and side-streets, dodging between scenic market squares and bars, and so, running parallel to it, in order to return to its beating heart.

Of course, as this was my first time in Brussels – and what a magnificent first time it was – Jo, a local – unconsciously and then consciously, started playing the part of the tour guide. And so, as the time wore on and we had taken a wider deviation from the path of the demonstration as was strictly necessary, our sight-lines began to broaden out, and even the manifestation seemed less important than a detail on a baroque church or any one of Jo’s favourite old haunts. I was very happy to be experiencing the city in this way – with him, with my magpie, flighty and strange, embracing the intertwining narratives of the day: the change in Belgium, the European swing to the right, the will to be free, the unconscious fall-away into love; everything in a swirl of movement and optimism.

It was some time before we re-found the crowd. We were not the only ones to play truant: some fatigued trade union workers had decided to duck out of the march for a while and stood outside a bar with Belgian beer in hand. But, by time we had passed the ornate Doric colonnade of the gilded ‘bourse’ – and for a second I could not help but remember the goriest passages from The Heart of Darkness and the sickening truth behind Belgium 19th century surge in economic power – the remainder of the protesters had almost reached the route’s end. Then for a moment, in the dying remnants of the day, thick in a crowd, among a flotilla of green vests, with the light shining through the cracks between protester’s shoulders and banners; I was filled with a sense of elation. We were literally marching towards a setting, golden sun, and while crackers hissed and popped around us I was filled with a conviction that things would really change and Europe would fight against the corporatized right-wing and the majority was united against them.

By the time that we reached Brussels Sud, the crowd began to disperse in a number of directions. However, I could sense a more particular and focused energy upon the streets in one direction. Somebody made a threatening comment to Jo – it was the first time that we had experienced any kind of aggression the entire day. Sure enough, when I looked up into the sky I could see them – two marauding, circling helicopters in the sky. At the end of a very wide and long boulevard in the centre I could see another type of crowd, and two large fire engines, shooting jets of water at those below. Water canons I thought to myself, that’s quite serious. The journalist in me couldn’t resist it.

Let’s see what’s happening! I cried to Jo.

So we bolted towards the eye of the storm, and as we ran down the road, we entered a new kind of landscape – one in which cars had been overturned by an angry mob, where youths suddenly, instinctively, removed their scarves and covered their faces. We almost reached the crowd when suddenly I saw a large pale cloud heading towards it. I was so mesmerized by its form, that it took me a while before I thought logically.

Tear gas! I shouted to Jo. Without thinking for a second, we turned around and started running back in the direction from which we had come. Tear gas is no fun.

I want to get to the front! I said, panting with excitement. The adrenaline had kicked in now.

I think I know a way! He cried, let me take you through the side streets.

Angry Protesters-turned-rioters

And so we continued to weave, but this time for a very different purpose. I wanted to get to the front of that angry crowd, I wanted to see why the police were using water canons.

So we ran, others, with covered faces ran near us, they shouted to each other in strange languages – there were no women among them. Mischief was most definitely abroad. We took a wide curve through a number of side streets beside the flea market; many of the streets here were deserted and drivers had abandoned their cars in the roads as the traffic build-up had been so bad. The only folk abroad had something to do with this rioting section of the protest – situated at its end, a little way off. Suddenly we curved back in. From a side-street I could see the crowd again. It was remarkable. We really were right at the front-line, just between the riot police holding their small plastic shields aloft and the crowd. Just at that moment the riot police were preparing to advance on the crowd. I looked down at the floor, sparkling in the late-evening sunset with the vague shimmer of moisture from the water canons. I saw blobs on the floor. For a moment I thought that they were loose brickwork. Then ‘crack’ I heard a loud sound – splitting rocks. It suddenly occurred to me that these were chunks of cement and bricks – missiles that the crowd were throwing at the police. I took a photograph – a beautiful one, of this scene – the protesters with covered faces on one side, the riot police on the other, and the heavy fallen debris between them. (Alas how I wish that I could show it to you – sadly, my phone with all of the pictures from that historic day were stolen one week later.)

Then Jo called to me – Kat, let’s get out of here, it’s too dangerous.

I was inclined to agree with him. So we turned back, skipping between parked cars and antique warehouses. Within five minutes we had left the manifestation and the scene of political entropy, behind us for good. It was time for some black coffee and a cigarette.