When Arnaud returned from his field trip in the Alps, he brought back home a surprise: a young, caramel-skinned Chilean boy named Alexandro. He had also just moved to Ghent, Arnaud explained to me, and hadn’t arranged any accommodation beforehand. Did I mind if he crashed at ours for a week? Of course I didn’t mind.

One week turned into two, two into three. Overall I believe that Alexandro stayed on one of Arnaud’s numerous spare mattresses, moored to our living room floor for just under a month. By the end of that period I believe he had become my best-friend in all of Ghent. He too sensed this connection and once told me that our friendship had quickly developed to the same level as that he shared with his favourite girl-friends in Chile. We could laugh easily, he explained, at each other and about silly things. And he was right.

One of Alexandro’s most obvious attributes is his intelligence. Of Chile’s vast population, he had been awarded one of only three annual Erasmus placements to come and study in abroad in Europe for a year. He is just one year my junior and completing his Masters degree, but explained to me, with an hint of well-merited pride in his voice that he had already been a paid teacher and lecturer at the state university in his country and been published on several occasions, between of course, studying himself, and discovering the abundant opportunities for self-expression and bad behaviour in Chile’s capital, Santiago.

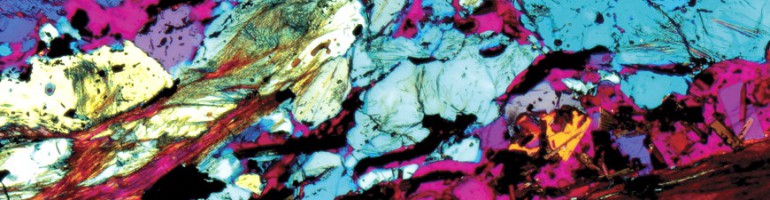

One explanation, I began to see, for the unnerving sharpness of his mind was the reasonably sheltered nature of the existence he lead before moving to Belgium. He did not like to drink, he had never taken drugs. His mother had lived solely for her children, and did everything for them: their laundry, their cooking. It was while he was encamped so innocently upon our living room floor that Alexandro discovered that just living for one’s self has a toll; and that self-provision takes time and money. I taught Alexandro how to cook pasta and use a record player. I helped him enhance his English, which was excellent and constantly refining itself (after two or three weeks in my company, even he recognised how fully he was able to pick up on all the nuances of almost everything I said). He taught me about electro music, social media sites and what individual beauty every single rock contains when seen closely enough, under a microscope. The jagged shapes and pools of fluorescent colour of these images, made me think of the kind of art that you find in psychedelic trance parties. But Alexandro was not just a kind of spiritual opposite; he challenged many of my values, eloquently and justly. In his company I felt that I was developing, and by gaining an insight into somebody who was resolutely of his era and no other, encountered an unflinching and powerful exponent of modernity.

Alexandro’s susceptibility to expensive and beautiful things, pandered to the Epicurean within me. So we ate out on multiple occasions and forged elaborate plans to travel around the Low Countries together – some of which we actually followed through on.

He provided key emotional support to me in the final days of the Dendermondse Steenweg; and filled an empty place that Arnaud had left beside me, for better or for worse. Yet his purity and his brazenness; his intelligence and his respect for the banal were an invigorating mixture which filled me with a refreshed sense of excitement about the city. Alexandro was a paradox of contending values: a young geologist who had been pushed into science when his heart lay with the arts. Yet his life’s ambition, he told me, was to excavate the beauty of geology for all to see; creating a kind of aesthetics of rocks. I loved this idea. Human beings already have a fascination for jewels and precious stones. Why not ordinary rocks? What degree of chiselling-down could enable us to see that everything is really at some level, beautiful?

I feel like I should write about Antwerp and Amsterdam – the cities that we visited together – or about Alexandro’s penchant for piscolas or his credo Be natural – which convinced me once and for all to return to my girlhood condition as a brunette; but now, all I want to write about is rocks.

Geology. The things that happen beneath us, invisibly, over thousands of years, the black chimneys of dust that circulate in the ocean at eight thousand metres water depth, the condition of the life that exists there; the heave and tug of continents.

Let us turn to a new scene: it was a sunny day in early October.

I needed to print out my tickets for the Eurostar in preparation for an immanent visit to London. But apropos of my departure I realised that all the printing shops were closed. Arnaud kindly offered to drive me to his office on the university campus where he is a PhD researcher, in order to print them out. It was to be our last expedition together – though at the time, I had no way of knowing that. When we finally arrived via the ring-road to the university campus by St Pieters Station – a vast, monolithic cement block – the entire building was deserted. It was a Sunday, and even the most lonely and industrious of the researches were not to be seen.

After scaling a number of immaculately polished, sand-blasted staircases, we finally reached Arnaud’s department which consisted of a number of rooms leading off from a central corridor. Though the atmosphere was rather sterile, I enjoyed looking into the display cases mounted on the walls hung with photographs from departmental expeditions, where groups of men and women were pictured standing together in the snow, smiling with hiking poles in hand or tightly buttoned up in thermal suits. Dog-eared contour maps and atlases ribbed with colour, added life here and there. As I walked around, I was reminded, and not for the first time in the presence of Arnaud, that both of my Russian grand-parents – now both dead – were geologists.

After completing the necessary tasks and raiding the department coffee cupboard, Arnaud beckoned me towards the microscope in his office. These specimens were the basis of his most recent paper and material that he showed students in tutorials, he explained to me. I blinked and peered into the upturned binoculars of the microscope but it had been such a long time since I had used a microscope (perhaps over ten years), that at first I struggled to see anything at all except a sea of misty white. Turn the nodule to focus the lens, Arnaud instructed, and nudged some bits of dust around on the petri dish beneath me with a pair of tweezers.

A wave of pure delight coursed through me. What to my naked eye looked like no more than the finest grains of colourless dust, materialised under the lens of the microscope to be sea-creatures as concrete and recognisable as the arthropods and fossilized crustaceans that you sometimes find locked in basalt or limestone in science museum exhibits. Ammonites – I believe they are called. Someone once, a long time ago, gave one to me as a gift.

My mind could offer no explanation of this incredible metamorphosis, and the secrete existence of organisms within particles so small that they could be scattered by a sneeze. Yet there they were before me with my super-annuated eyes; forms that both were and were not, with discernible characteristics such as spiral shells and legs. The art historian within me felt very humbled. I had always accorded such a high place to the visual arts, to the things you can see with your eyes. Yet this organic quantum mechanics made me realise that there was beauty in everything. It was just a question of looking hard enough.

As Arnaud began to deliver an explanation of some of the features of these specimens, sketching the conditions of life at 8,000 metres water depth, and drawing yet more dust motes from a variety of glass phials, my mind drifted towards the great writer and marine biology enthusiast John Steinbeck. I thought of his life-long friendship with the scientist Ed Ricketts, whose big heart and love of the natural world was commemorated in his books in various forms. The Log from The Sea of Cortez is Steinbeck’s great tribute to Ricketts and contains many anecdotes about their rock-pooling expeditions and field-trips together. I recalled this wonderful quotation:

“[…] it is a strange thing that most of the feeling we call religious, most of the mystical outcrying which is one of the most prized and used and desired reactions of our species, is really the understanding and the attempt to say that man is related to the whole thing, related inextricably to all reality, known and unknowable. This is a simple thing to say, but the profound feeling of it made a Jesus, a St. Augustine, a St. Francis, a Roger Bacon, a Charles Darwin, and an Einstein. Each of them in his own tempo and with his own voice discovered and reaffirmed with astonishment the knowledge that all things are one thing and that one thing is all things—plankton, a shimmering phosphorescence on the sea and the spinning planets and an expanding universe, all bound together by the elastic string of time. It is advisable to look from the tide pool to the stars and then back to the tide pool again.”

Sitting together in the deserted office, I could also not help but think back to a recent chance encounter that I had with a geneticist and researcher at The Volks Huis. Making the most of an, at first not promising Thursday night, this man entertained me for hours with hair-raising stories about his field-work in Turkey. He was a geneticist, but a genetic archaeologist, who extracted information from fossilised fish bones to try and ascertain facts about the shoals of tuna fish that used to populate the waters of Constantinople. Some phrases are seared indelibly into my mind. He said, that first-hand accounts from the people who lived at that time, recorded sightings of shoals of giant tuna fish that were so great in number that they were described as herds. The Bosphorous was not lagoon-blue, but on some occasions white, thick with the bodies of tuna-fish that jostled together in its waters. To over-fish was an impossibility. The surfeit and over-abundance of fish was like a god-granted miracle. Then his friend appeared, who took over the story-telling lead and regaled us all with tales of his exploits in Israel and Gaza while on a dangerous undercover documentary film shoot there. He spoke of in-fighting between the anarchists, police violence and intimidation; harrowing arrests at night. They were a very high-powered pair.

But back to geology. In the end we left and Arnaud had succeeding in instilling in me a burning curiosity and interest in his subject – the mark of all good teachers. By the time we stood in the university campus car park and had slammed the doors of his Renaut shut, I knew that these coincidences had to amount to something and that it was time to write a story that had been lying dormant within me for some months. It was the story of the glass-maker Leopold Blaschka and the marine glass sculptures he made following a long voyage across the Atlantic Ocean.