Two nights ago I went to see Christopher Nolan’s masterpiece at the Scoop Cinema in Ghent. It was not the first time I had been to the cinema – I had already visited on a few occasions during the Ghent Film Festival; but it was the first time that I felt inspired enough about my time there to write about it.

Any real cinema buff would be delighted by Scoop. It is a large, draughty building on the Sint-Annasplein, not far from the lurid incarnadine city lights of Ghent’s very own Red Light District. Situated on the edge of the scenic roundabout – also very near to the Bibliotheek – and at the inception of the beautifully-named Violette-Lange Straat, for me Scoop is has always been poised at the edge of the recognisable world. Its limit is the cinematic limit – which is actually no limit – as Nolan’s film demonstrates so well. There is no space that film cannot represent, just, as I suppose, there is no space that literature cannot re-create or create, at least in theory.

What distinguishes a really unique cinema from the run-of-the-mill over-priced art house cinema? As I used to have a boyfriend who took pleasure in unearthing Art Deco cinemas across the UK, I feel I have some idea. The main tenet is that charm and not profit is the operational driving force behind the institution. So great cinemas – like the Cowley Picture House in Oxford – with noisy aluminium fold-out chairs instead of upholstered stools, will always claim first place in my heart. Of course, it’s not just about aesthetics. I wonder if any cinemas are now left in the UK which still use 33mm. The shift towards digital happened so rapidly and comprehensively that there was barely a swan song for the highly impractical, clunking cinematic reel – an object that I fear will even be an art object and collector’s item in a few year’s time. I remember a great film critic at Edinburgh University – Martine Beugnet – once speaking very poignantly about the death of 33mm. It is not the transition or upgrade. It is the death of one medium as we know it. Cinema, as it was originally conceived, no longer exists. What, one might reply, is the material difference between a digital and analogue image? Who cares if the apparatus is different? Well, Martine, would reply, many things. To take one example, digital film cannot reproduce the same tonality of black as 33 mm. Velvety blackness was how she put it.

So Scoop is large, draughty building on a roundabout formed from the hollowed-out shell of two or three adjoining 19th century townhouses. The auditoriums are not especially grand but have the requisite ruby-red stalls for seating. Screen one is the exception as there are a number of fin-de-siecle inspired mermaids drifting among a wall colonnade. But it is the atmosphere of the place as a whole that I love: it is a vast cinemapolis, a cinematic maze, but with the dishevelled vibe of a surburban garage. In the corridors, vintage movie posters peel on faded-apricot walls. The box-office girl, with two fish-tails of red lipstick, will print out tiny ticket-stubs on madder pink sugar paper. It is all so typically understated and chic. And then the bar — I have sometimes wanted to watch films at Scoop just for the post-film run-down afterwards. It is a narrow space with an extremely high ceiling and mezzanine floor. The slender stairs to ascend it are so steep that they are almost a ladder. The heavy, varnished tables; the slinking, silhouetted figures at the bar. This is certainly a venue where the Flemish literati appear in all their vanquishing brilliance and beauty.

However, it is not only the architectural and aesthetic virtues of the cinema that I adore, but also their programming culture. It is almost impossible to keep up to speed on the myriad number of films screening at Scoop. There are often simply announced on two A4 print-outs bluetacked to the box office window.Comprehensive listings very difficult to negotiate online. So I feel that my cinematic experience at Scoop is very much like the old days: I will turn up at 7.45 and pick which of the five films showing at that time most tickles my fancy. The films are on a fast enough rotation to ensure that this exercise never becomes stale. So I rarely go to Scoop with a plan to see a particular film. Instead I go in good faith that the cinema will supply me with something – and it always does. Of the five different films screening at 8, any number of them will be off-the-beaten-track prize winners, well received at Cannes or Berlin, beloved of critics but not the mainstream. I suppose the programming culture of the cinema could be described as a little pretentious – or at least especially discerning. Last year’s La Grande Bellezza has had an unbelievably protracted run. I believe they still screen it every week for the acoloytes and modern aesthetes to whom it is their non plus ultra.

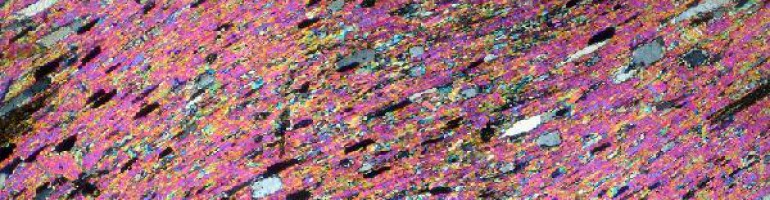

Interstellar is the only film that I have ever seen twice there. The first time, with the Magpie, we roosted irreverently in the front row, kicking our feet up in the air and taking occasional puffs from our e-cigarettes. The second time was very different, I was with one of the Ghent scenesters, a young entrepreneur who wore more black and leather than a new-age Goth. He was not very moved by the film – why was I? Despite the fact that it was such a big American production, pictorially I felt it was a throw-back to the Cold War era of cinema. The grainy picture quality, the reliquary of Sov-tech machinery, all seemed inspired by photographs of the 1960s Space Race. So its very futurism was nostalgic. Does that make sense? Its allegorical qualities too, reminded me of Tarkovsky — especially that wonderful sequence where Cooper is transported into the black hole, below or beyond a quantum mechanical horizon. It felt to me like Cinema at its most abstract and metaphysical – and therefore, also, at its most poetic. It was meta-cinema. Nolan was flirting with the outer possibilities of his chosen form. To represent the unrepresentable – a space outside of time and the conventional laws of physics. Then there was the clever link with the book-shelf. For me it was a powerful metaphor for the limitless possibilities of art in general. I am reminded, perhaps for no very good reason, of that famous Hawking-derived idea: The limit of human endeavour is only the limit of our own imaginations. So bravo Nolan – aside from the ending, too trite – quite an achievement.