Ghosting around the city – there is one landmark where my shadow rests more frequently than others. It is a place I come to often and love, about which any account of my time in Ghent would be incomplete without mentioning. It is also a place that I would recommend to visit if you are ever passing through – a textual mecca that should be on every bibliophiles tourist map.

The public library of Ghent is an imposing white structure located in the southern quarter of the city, a stone’s throw from the Leie river. It was probably built in the sixties and has a vaguely futuristic aura – with funky architectural features such as a curving roof façade supported by unashamedly minimalist cement pillars. Above the library foyer scrolls across the library name: bibliotheek. This slanting lower case signage of has always symbolised the library’s (in Derridean terms) difference to me. For the public library of Ghent is different: cooler, hipper and more slanted than any other library I have ever known.

The bulk of the library is attached behind the large proscenium which houses the library foyer. It is supported on this narrow white colon like a shell on a snail’s back. A less-than-appealing grey block, visually its merits can be judged better from the inside than the outside. On a clear day, views from the fifth floor desks are staggering: you are able to see right over the top of the spires of Gent centre’s famous ‘three towers’ – the Belfry (‘Belfort’), St Bavo’s Cathedral and St Nicholas’ Church, passed the ESB factory chimney towards industrial skyline of the Handelsdock. The librarians who work on the fifth floor in the ‘music’ section, also have exceptionally good taste. While I have written and researched quietly at my desk, I have subliminally taken in whole music history lessons. There is a serious bald man who likes to play Mendelssohn, while the young man wearing square glasses prefers Americana and folk.

What makes this library so singular and lovable? When I first started working at the library I used to sit in a well-lit corridor suspended above the foyer on the first floor. Flooded with light from the glass walls surrounding it, this corridor is purpose-built for newspaper lovers. Here, newspapers from all around the world are stacked up in central racks, free to peruse at your leisure. The diversity on offer (Belgian newspapers, French newspapers, German newspapers, British newspapers) testifies to the city’s poly-linguistic character and the wide margin of languages that almost everyone can speak in Northern Flanders. This comes as a result of its geographical situation as much as anything else, sandwiched between some of the largest media economies in Europe, Germany and France. The newspaper lounge is distinctly civilised place to pass an afternoon. No computers are allowed on the plain white desks arranged along the walkway, so a quietness settles over everything interrupted only briefly by the whizzing of the coffee grinder from nearby library café.

I love to read British and French newspapers in this place, flicking through the pages of Le Soir or cramming in a Times quick crossword. I people-watch out of the corner of my eye; it is like a vision from a past world: lovely old gents shift about in two-piece suits and squint at desks. Poe-faced students sit tuck into film reviews. Dishevelled, evil-smelling figures lie sleeping undisturbed: no paper at all before them.

The Bibliotheek’s final great attribute is the canteen run by a husband and wife team. The food isn’t the real draw but the coffee is strong and always served with a slab of dark chocolate. I’ve reeled off whole stories sitting in the covered veranda terrace level with the plane trees, overlooking the tram lines and bus stops beneath. It is a chaotic part of the city, but also a place where movement, transport and the city life acts as a source of inspiration, reminding me of the Impressionists’ renderings of Haussmann’s Paris. The facades of enormous neoclassical city-houses spring up in the distance. I feel like I am transported back to a giddy 1940s metropolitan utopia squeaking with motor-cars.

These are just some of the things that make the Bibliotheek a special place for me. But I am by no means alone in feeling this way about the library. It is always full. Its popularity demonstrates that it is a public resource for learning and education that is used and loved by all the people that live in the city. It is a facility for learning – that unlike the British Library – does not exclude. Membership is free, wifi is free. For me, there could be no better example of a successful civic project, a public space designed and maintained with such thoughtfulness and care that it does not only facilitate other people’s learning, but actively encourages it too.

An Historical Digression: The Libraries of Oxford

I have often thought that one of the only things that ties me to civilization is the existence of libraries. Life without a really good library nearby either public or one that you own, seems deeply impoverished. I remember a quote pinned up on the wall of my father’s office: “Reading a good book is like having a conversation with some of the finest men of the past.” And whatever else my family home has come to symbolise to me over the years, it has always been, among many other things, a library. Indeed, one of the earliest photographs that I have seen of myself as a toddler – with hair sheared back like a boys and gappy milk teeth – I am busy gleefully undermining my Dad’s insistence on alphabetical order in the family bookshelf. Equally, memories of my father standing before me with a jigsaw and spirit level, indoctrinating me in the art of how to put up a level shelf, was one of my earliest wood-work lessons.

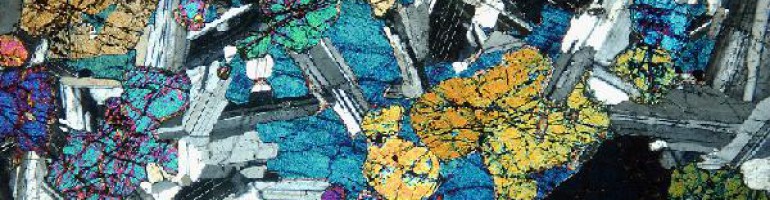

Over the years, the current of books has been re-directed towards many unlikely sources: second hand shops, car boot sales and forgetful friends’ houses; yet still the vast bulk remain churning about in the family domicile, moving from room to room and recording the tide of influence, age and recommendation, like the alluvial and changeable mass of sedimentation that it is.

Oxford was to me, one huge library resource. Indeed, rather than trusting in league tables, I have come to think that we can rate our universities merely on the quality content-holding of their libraries. It was in Oxford then, that the habit of attending different libraries – all of the best ones which strangely, had nothing to do with the English faculty – that I began to experience the pure joy of library dilettantism. There I became a kind of library tourist or nomad; one for whom the limited means of creative choice I could exercise over the course of my everyday life due to the heavy workload, began to express itself in terms of working context. The lower floor of the Radcliffe camera – gloomy, cavernous and as its name implies camera, in the round – was my first port of call. Many of my best-friends worked there, and if you arrived when it opened at eight or nine in the morning, you could secure the best seat – a window seat, that permitted a view over Radcliffe square. I remember peering up at the enormous windows both at day and night and thinking that the crescent of rails displayed in fan-like fashion in the transom window, resembled the spokes of chariot wheels. However its austere interior, thick with leather upholstered seats and studious readers, often made me feel so lethargic that I struggled to stay awake and refocus on Walter Pater. These narcoleptic tendencies prompted me to become more experimental. I tried the upper storey of the rad-cam first, but its palatially high-domed roof and alabaster white walls, was too grand for me. I felt like I had got lost in a Hellenistic day-dream; plus the wooden desks squeaked when you wrote on them.

For convenience’s sake, especially during exam season, I started working in the Bodleian. My room of choice was full of Middle-English manuscripts. These tomes were chained to their places high above the desks and bore down like heavy crowns upon the heads of white-haired academics studiously bent beneath them. A view from the window, looked down upon the autumn-leave speckled grounds of Brasenose college, revealed a college park that was always strangely empty. Most students did not work in or perhaps even know about this beautiful room in the Bodlean. I only went there after a tip-off from another English graduate.

Then one day, I found it by pure accident: the library I had been waiting for. It was the university’s philosophy library, located not far from Magdalene College. It was established in an old town house, in a decrepit buildings whose mullioned windows were festooned with ivy and creepers. This tilting house of books felt jumbled and disorganised, and it pleased me that the volumes it contained were not mounted austerely between Hellenistic columns or in the vaults of the lower-cam, but on ordinary walls in pokey rooms. I could imagine Lewis Carroll pencilling down self-humouring postulates of logic here or devoting himself to his secret passion: photography.

I left, but vowed to return. Then like an hidden annexe in an enchanted castle, it suddenly vanished, and I was never able to find it again.