I first started compiling and archiving entries under my blog Time Signatures two years ago. As the title of this blog suggests – temporality – and trying to understand its relationship with writing, was of central concern to the project. I was deeply influenced by my reading of Benjamin at Edinburgh University in 2012, especially his account of the individual’s relationship with the historical process. This obsession with time and temporality had a bearing upon a central – or as I then saw it – paradox, that affects all forms of writing, but especially the blogging form; i.e. that disjunct between the moment of experience and the moment of expressing or recording it. My interest in temporality and writing – the run-away moment – was also a subconscious extension of the manner in which that particular blog came into being. The critic and writer Richard Mabey talks about “secondary nature”; well the material on Time Signatures was largely, “secondary travel writing”: a repurposing of slightly less polished accounts that I had sent out to friends via email the year before. Hence, at the point at which I was constructing Time Signatures – laying together the disparate bricks of a travelogue from two years preceding – I had the uncanny sensation of feeling that the experiences that were written in the ever-unfolding present, were actually displaced by several degrees – through processes of reception and reformation, over a distance of several years, even geographically distant from their original places of conception. What meaning did they contain and what sense could I make of being their ‘author’; I who was now displaced, relocated, constantly adjusted by new environments and experiences?

The question of temporality’s relation with literature seemed highly pertinent to me then: it seemed to beg wider questions about how humans can relate to their pasts, their ‘histories’ and how we relate to the texts that we produce. I felt a great sense of sympathy for authors who had been vilified for the opinions that they had expressed in their youth. It seemed asinine that in human life we expect people’s opinions to grow and develop, but in the world of texts the opposite is true: authors are locked down to the statementing myths that the public want to remember them for. But on the other hand, it’s important that there is some accountability, right?

As a way of trying to break down the temporal wall that built up between the moment and its record, I experimented with a Dadaist technique that I read about in an art textbook called Ecriture Automatique. ‘Automatic Writing’ was reflexive, instantaneous – it was language ripped from the present moment. So I tried to write as much as I could from within the experience itself – and the difference between this sort of text, and the texts written in hindsight or in diarist style are immediately obvious.

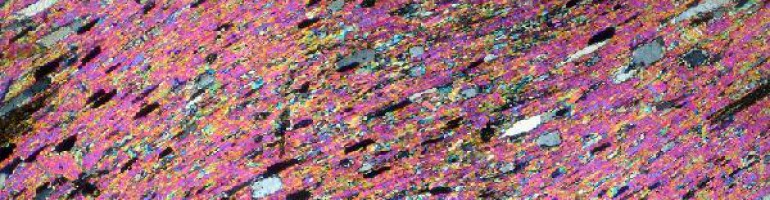

More recently in Ghent, I had fresh cause to think about the relationship between time and literature. In the past my écriture automatique had always, of necessity, been bucolic. As long as my subject didn’t talk to me or require any interaction with it: I was able to write it, to paint it, automatically, with language. Thus I was able to record scenes or the fluctuating sensations of my own subjectivity and inner sensibility, I was able the checkerboard of colours that I saw in the Gobi desert from out of my Jeep window – or the ‘panorama’ of Siberia flashing past my train window. The subject was always passive, not active.

But one morning, in Ghent, while sitting round my kitchen table, I was actually able to paint a social interaction between myself and a young man who was open to the experiment (and possibly a little high), so that I was able to write it – the conversation – while only ‘umming’ and ‘ahhing’ occasionally.

At the time it felt like I was breaking through something. I had grafted the moment itself onto the record. I had eroded the membrane that stands between art and reality to its narrowest possible point. The art was inextricable from its context, the context of the passing moment. It was ‘action writing’.

But that breakfast conversation also gave me another reason to pause for thought. Drugs. They are everywhere: ubiquitous and forbidden, a part of our simulacrum and the escapist-hedonism drenched postmodern world. It made me wonder, what was the difference between the young day-tripper sitting opposite me – his mind permanently awash with displaced fantasies – and myself? Isn’t the writer, like the day-tripper, also an escapist, a dreamer, a professional fantasist? Suddenly it seemed that all of this temporal displacement and self-dissolution was eerily similar to some kind of socially acceptable trip.

Society had developed different ways of thinking about people who hallucinate or fantasize regularly. More often than not we pity them for their powerlessness – we consider them winsome misfits, perhaps mad or unhappy. So if the writer is a professional fantasist, she is also a madwoman or a depressive – both figures that have been marginalised in European societies: institutionalised, stigmatised and removed from view. Why are dreamers so dangerous for society? According to Aristotle the poet is politically dangerous and threatens the very fabric of the Republic. Dreamers are dangerous because they are still. Perhaps stillness is in itself is a kind of disobedience. It is not very easy to day-dream in London. There’s too much interference – too much going on, too much money everywhere. But on a boat or among the larch trees of Ghent, it is very easy to dream…

The more I write and think about it, the more obvious the oft-discussed correlation between madness and artists appears to me. Displacement, self-effacement are part of the job description! And artists who have openly depended on drugs for success? They are too numerous to count. There are obviously hundreds of musicians, and writers… well the Romantics are the obvious examples. Thomas de Quincey made opium a theme in his writing – and what writing it was! His essays are some of the most beautiful and elegant prose works I have ever read and his writing on the mind as palimpsest, one of the earliest anthologized attempts to grope towards a modern understanding of the human brain. I also remember reading a contemporaries’ account of how the opium ‘dribbled’ from the mouth of William Hazlitt – probably by someone like Dorothy Wordsworth.

Of course this is not a defence of recreational drug-use for the purposes of artistic expression. I have come round to the view that mental well-being is one of the most important assets that we have – we need to protect our minds. In fact, the more I think about drunk, coke-snorting city workers, the more I think that the proliferation of drugs in modern society is capitalism’s ultimate triumph. We are all self-medicating on opium.

So, I have considered different models for thinking about the writer: as time-traveller, as fantasist or madman. But these are unsatisfying; they seem too cynical, too irrational. After all, writing doesn’t have to be retardant – it can liberate itself into infinite possible futures.

So perhaps we should think of writers instead as astronauts – alien way-farers – jumping between lunar islands of present and possible futures. It’s all good of course, could even be terrific, so long as the spaceships land back down on earth.