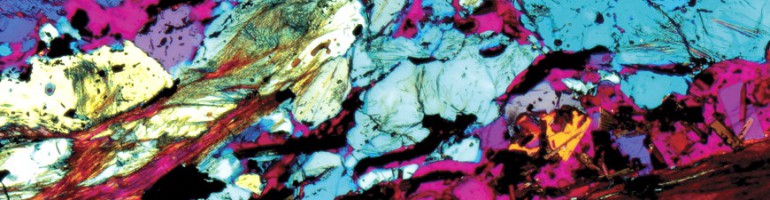

Detail from the central tympanum of Antwerp’s Cathedral of Our Lady.

It’s spring now. Did you notice? I did – March showers: sudden, elastic, tragic; volleying and pounding little plastic balls of hail onto my woollen hat. I was like that today as I rain-danced and jogged through the tired streets of Robot, adulating with Turkish ‘bakerijs’, posters of pitta bread brimful of shis kebab. If you go far enough you get to the Gent-Brugge canal – if you go even further you get to Bergoyen: my garden, my retreat, my lake.

I came that way two days ago with Davilo – the Argentine that I met at the pub, that night a thousand years ago. I found out that he played music – I asked him if he knew La Compasita. It was originally an Argentine folk melody and the magpie’s next project. He said he played it since he was a little boy. I immediately invited him to my kitchen where I imagined him sitting happily beside the magpie, strumming together in unison like an old time Spanish guitar duo or like the Prodigal son returned.

It was never to be. Did he lie to me? I don’t know – but he couldn’t play La Compasita. The magpie slouched, the request died on my lips. But he could do something much, much better than play this tune. He could talk about the mind. He could talk about the mind coherently and with complete confidence. I don’t think, actually, that I have ever met such an eloquent foreign English speaker – his capacity to shape ideas, mould them and refine them as he spoke, in a language not his own astonished me. It was far more impressive that a virtuoso guitar solo. It was a brain, a brain virtually pumping with a sense of its own brilliance.

I would love to plagiarise. I would love to – right now – tell you all the brilliant things that he told me. But even as I do so the efforts fail before I even begin. How could I hope to convey those sparkling, jagged, fragments of conversational mirror that I could barely understand at that time – and if I did so, only fleetingly and lovingly, like a child grasping at snowflakes in the air? Davilo’s mind is voracious, greedy, self-devouring. It never stopped. As soon as he had formulated one idea, his was busy composing his next. It reminded me of something a friend once said to me: she said that while others wrote or painted or acted, she considered her life’s great works to be her conversations. That was where she had stamped her finest intellectual achievements. Her masterpieces was relational, performative; they were perlocutionary.

I remember the first afternoon that Davilo came to see me alone. He was barely through the door when his strange form of monologuing began. We had both been away for a few days. It is strange, he said, since I came back I feel that everyone in my life has taken some big steps forward in the past two weeks. They have made discoveries or decisions that have changed their lives, and not in small ways. It is very queer.” No hello, no kiss on the cheek – right to the heart of the matter. Then of course I asked him what life-changing events had taken place in his internal world since I saw him last. He was vaguer in this regard – threw some hints my way – Czechoslovakia, hugging a stranger in the dark. They had so much in common that it was uncanny: like a glitch or knot in fabric of things.

We weren’t talking, we were metatalking, we were talking about talking. Words spun around like fireworks or a gambler’s die. We were sculpting something together, something precarious and liable to fall – but only if he let it. He never did. So we started talking about talking again: I mentioned our exchange as an example. Ah no, but it’s different between you and I, he said. We are not playing by the normal rules. We have made a contract – an agreement – not to follow the usual rules. His certainty made me doubt. What contract had I signed with him? What kind of language did we use with each other that transcended the usual – presumably moribund – delimitations of human speech? I had the sense that it didn’t matter where we were (as it happens at my kitchen table). We could have been anywhere or nowhere. At that moment in time everything was telescoped down to just one discernible point: his moving mouth. The ventriloquist. The tea got cold in the pot. I didn’t even pour it.

We cycled to Bergoyen by the water in the late afternoon. By the time that we got there the sky was resplendent: the setting sun had cast a rose-red light across the whole meadow. Again the words poured from the cataract of his moving mouth: we all carry round a burden of guilt and shame: it is part of our inheritance. Why carry it? Let it go. What is talking? What is friendship? I asked him. Communication is nothing but a rough translation. Friendship is assessing the extent to which your language maps onto mine, my Orpheus replied. We live in a culture where stress and intoxication are predominant. Why is that so? I asked him. I don’t believe that people forget the things that they do when they are drunk, it is precisely to do those things that people drink in the first place. Intoxication is a permission-slip, it allows us to do the things we desire but fear to do ordinarily. What is your view of London? I asked him. I liked London he replied. When I went there I felt oddly at home, people were very receptive to me. But the people who live there – they are some of the most over-worked people in the world. We had zapped into a different dimension where everything ceased to matter except for our minds and the slippery quick-silver snakes of his psyche. Why try so hard? He said. It all amounts to the same thing. That’s what I learnt. Anxiety, shame, greed. We don’t need to live with shame in our lives. Other people? They are an illusion. I have been reading recently Jung’s theory of the shadow. He predicts that our evaluations and anxieties concerning other people are almost certainly projections. They are our shadows, what we project onto them are our own shortcomings.

I had taken him to Bergoyen for a reason. I wanted to impress him – to show him something secret and magical, something I treasured. It seemed to barely register: the low white sun, the grey, glossy meadow-lake, the flocks of birds nesting in the long grass. Yet this time it began to chaff. As brilliant as he was I wanted to tug this intellectual troglodyte from out of his mental cave. See the world around you! Something inside me cried, though I was too afraid to say so out loud.

The more I analysed the auto-didact Davilo and his persuasive way of talking, the more I realised that he was a product of therapy, therapy conducive, perhaps not to one’s mental health but to one’s ability to articulate and atomise oneself and the world around you. It is a great skill. Now that I come to think of it some of my closest friends have undergone extensive therapy and thus had an opportunity to fine-tune that highly undervalued skill: the art of conversation from a psychological point of view.

But Davilo is not alone, he is only one of many common-place geniuses that I have met in Ghent. It is a city which, I began to realise, attracted extreme and eccentric types, like the local postman who was able to play every middle-eastern instrument I could name, and could speak with more ease and clarity about the abstract qualities of music than most people use to speak about their grocery shopping.

We cycled back, it was time for work. Somehow something in me was unsatisfied. I tried to reach out to him, to talk about him, my frustration with his inertia, his depression, his inability to realise his dreams. You are not talking about him. He are talking about yourself. Remember the shadow? Penumbra. He is your mirror. It was not cold, just objective.

I was stunned – appalled. The truth of this judgement fell on me like a weight of bricks. Had I become him? After all these months of writing and vegetating in the spell-binding voluptuous setting of Prinsenhof, like the little figurine in the centre of the music-box? He was right. I was the magpie. Nothing more; nothing less. A mirror somewhere shattered. I was illuminated; exhausted and totally unhappy.