Day Three

The Streets of the Seydisfjordur

We woke up to a white world – snow lay twenty centimetres deep on everything: the pavements, car bonnets, rooftops. Though it was beautiful it also rung a little warning bell in my mind: even in Iceland snow showers shouldn’t be falling in May. It was highly unusual and probably the result of climate change. It reminds me that one month on the verdict was officially out; the winter of 2014-15 had been one of the hardest in Iceland for over thirty years. Anyway, despite the snow we all felt it was high time to begin exploring the town. I had a little treasure hunt of my own that I wanted to follow up on. Funnily enough, the preceding day, as we were braving the mountain pass, a thought had occurred to me. The thought has its origins in a gallery retrospective that I had visited in Berlin in 2014, all about the life and work of the avant-garde American artist Dorothy Iannone. Well, I vividly remember reading one of her graphic novels whimsically named ‘An Icelandic Saga’. The saga described a love story between the painter and her Swiss lover Dieter Roth whom she first met with her husband in the 70s. Leaving everything behind in America, Dorothy decided to live with Dieter in his artist residence in Iceland for several years. I remember reading elsewhere in the gallery that though this passionate love story was eventually to come to an end and Dorothy pick up sticks and live elsewhere (India I believe), she always remembered Dieter as the true love of her life. He must have been a very charismatic man. Anyway, en route to Seyðisfjörður, a small outpost in the east with a reputation for attracting artists and craftspeople, I caught myself thinking: I wonder if this is where Dorothy and Dieter lived together. It’s where I would have chosen, if I had been them. Reyjavik was too obvious, too mainstream. They wanted to disappear from the eye of the world; to devote themselves just to each other and art. Where better than here? A place entirely cut off from the rest of the world, nestling in the side of a mountain and looking out towards Norway.

On a hunch I asked the receptionist at the hostel, who, amazingly confirmed that Dieter did indeed live in the town with Dorothy. He continued to live there after she left him and many of his family members still lived there. I asked her if she knew him personally, she shook her head. It was before my time, she said. But people always said that he was a difficult man; brilliant but hard. I asked her what happened to him. Her eyes met mine, he drank himself to death. There is a video, he filmed it, filmed the whole thing. He filmed his death. I shuddered, it must have been a terribly painful and lonely way to die. Do you know where they lived together? I asked her. Yes, by the old harbour, in a small house there by the water’s edge. If you get lost, just ask, everyone in town knows it. I thanked her and then left with the others. After visiting the town church and idling along in snow-laden streets I decided to leave the others and head for the old harbour. I wanted to be alone there.

Seydisfjordur Church

Two people passed by: black figures in the snow, there was a little girl too I remember. They both looked at me curiously, standing in someone’s front garden looking out towards a solitary brown cabin with a small jetty at the waters edge.

Dieter’s House: At the End of the Jetty

There wasn’t a sound to be heard, except the soft brushing of the snow and the uncertain tread of my feet. Streets and roads no longer existed, it was just trial and error. There was something about the little cabin, modest, romantically situated, which filled me with sadness. I tried to imagine their love there; their absolute and total insularity from the rest of the world. They were both such fiercely talented people, yet their lives must have been full of silence. I thought of the way that Dieter killed himself. I had to turn away. I walked slowly back to the guesthouse.

Dieter’s Cabin: Detail

The others were excited when I met them again. We have just been to the Skaftfell Café – it was full of interesting artist prints etc. They asked me if I had found Dieter’s cabin, I nodded. Actually, if you want we can go back there, there were quite a lot of artist books on the shelves. Back out we went. While I had been filling in the missing puzzle pieces of Dieter and Dorothy’s life, so had they. I almost couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw a line of Dieter’s colour etchings and prints hanging up on the wall – though there was nothing of Dorothy’s there.

Dieter’s Prints in Skaftfell, Centre for Visual Art

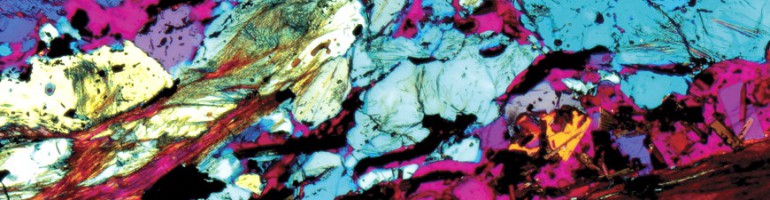

The prints were interesting, full of contorted, biomorphic forms swirling with body parts. They were both, after all, erotic artists, or at least artists who frequently used the body as a metaphor for other ideas and themes. In Dorothy’s work particularly, sex is always there: in a dark, magical, transcendental sense; an emblem of the self, of the absolute, of the deep life that exists within.

Detail of Prints: Mangled Bodies

I flicked open a hard-back. It was a collection of the love letters they sent to one another, mostly type-written. There were cursory, brief, full of the short-hand and sweet little names that lovers use with each other. It felt almost too close, too revealing. I closed the book and looked outside: it was still snowing.

As the nursery rhyme has it, what goes up must come down. We knew that to get home that evening we needed to ford the terrible summit once more. If it was scary before, I couldn’t imagine what it would be like up there now: it hadn’t stopped snowing once since last night. And it was getting on: already midday. We all knew we had to get moving and leave Seyðisfjörður though we were enjoying ourselves. I looked at our pitiful vehicle parked outside: it was a car designed for cities and highways, not deep snow and icy roads, but we had no choice. Luckily for us an American couple from the hostel were also leaving that afternoon. We decided to team up. As they had a robust 4×4 they would lead the way and we would follow behind. As we slowly ascended the mountain leaving the town behind us, I had my first real experience of tough Icelandic driving conditions. The blizzard was thick and visibility was very bad, aside from the yellow markers that threatened to disappear into piles of snow, the road was impossible to see. We drove very slowly, following marker by marker. At its worst points, we could only see one marker ahead of the car. At one moment, the 4×4 was forced to stop as our brave American couple couldn’t see the road ahead of them at all: it was just a huge wall of white, might as well have been an avalanche for all we knew.

Driving in the Snow: On the Way Down

That journey seemed to last forever, all the while my eyes were trained on the distance, watching out for oncoming vehicles. None came. We were probably the last cars to make it that day, before the road was deemed impassable. When we got down to Egilsstaðir we had great trouble fixing a homeward route as the excellent roadconditions.is website was quickly narrowing down our options: roads all around us were on ‘yellow’ alert i.e. slippery but still passable. More and more were becoming red or ‘impassable’. At one point, we were forced to turn back on a very difficult ‘yellow’ road because a huge snow drift had made it impassable at one end. It was very dispiriting to turn back after 40 minutes of driving and return to Egilsstadir along a road that was already testing our driver and vehicle to its absolute limits.

The Lake at Egilsstadir

Anyway, I don’t want to speak about cars and driving anymore. You get the picture. However, because of Dieter, delays and snow we didn’t arrive to our final destination for the road trip – a farm with Jacuzzi – until very late that night. Then midnight dip beneath the stars, soothed us into shape for our pillows and a long, deep night’s rest.

Leaving the East Fjords

![By [www.flickr.com/photos/davidstanleytravel/ David Stanley from Reykjavík, Iceland] (Flickr) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://833wordsaday.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/reykjavc3adk_-_botanical_gardens.jpg?w=300&h=225)